Feeling social: Technology and travel group in tourist experience

1 Introduction

Studying wireless internet connectivity has become a priority for leisure academics. Over a quarter of the world population uses a smartphone, the most common device for wireless connectivity (Curtis, 2014). For the purpose of this study, wireless internet connectivity is defined as connecting to the internet over wireless signals, often on mobile devices. Mobile devices include smartphones and tablets, as well as occasional watches or cameras, and their constituent software, such as social media platforms. In the present study, we examine the effect of wireless internet use in general and social media use in particular on tourists' experiences.

While marketing has been a focus of tourism research on wireless internet use, according to Molz and Paris (2013, p. 190) "the spread of smartphones, portable computers, and social media and networking technologies marks a transformation in the way people travel and the world in which they travel.” Thus, not only tourism marketing has changed, but also the tourism experience. Transformative changes in the tourist experience include the way tourists fill downtime, collect information, and make decisions (Wang, Xiang, & Fesenmaier, 2016). While several retrospective studies of wireless connectivity, mobile devices, and social media in the tourist experience exist, there is much to learn (Wang, Park, & Fesenmaier, 2012). The technological revolution has led us from maps and a compass to GPS and route planners, from ringing doorbells to Airbnb, and from writing a postcard to family back home to video calls. The experience of travel has changed and the consequences of this change are not yet clear. Specifically, the goal of the present study is to explain how two commonly discussed aspects of mobile connected technology - time spent connected to wireless internet and social media - influence the tourist experience.

We chose to focus on tourists’ emotions as a crucial aspect of their experiences. Emotions embody the extent to which tourists enjoy or take pleasure in their activities (Mitas, Yarnal, Adams, & Ram, 2012a). Emotions are a key ingredient in tourist experience marketing (Song, Ahn, & Lee, 2015) and design (Tussyadiah, 2014), and can be seen as the source of value in most if not all tourism experiences (Mitas, Nawijn, & Jongsma, 2016). As Mitas et al. (2016) point out, of several possible dimensions of emotions, positive emotions have been emphasized in tourism research. Positive emotions are more visible compared to negative emotions in most tourism marketing as well as tourism experiences themselves (Hosany, Prayag, Deesilatham, Causevic, & Odeh, 2015). Most previous studies of tourists’ wireless internet and social media use have focused on provision of information. While information is important for making decisions, information provision addresses only a small proportion of tourists’ overall experiences while traveling. Thus, it was urgent to find out if tourists with greater wireless internet and social media use also experience more positive emotions.

Furthermore, experiences may differ for solo and accompanied tourists. Solo tourists are away from their home, friends and family, possibly interfering with the positive emotions that characterize most tourism experiences. Social media and smartphone calling and messaging apps decrease social distance, however, perhaps attenuating effects of traveling alone on positive emotions (Büscher, Urry, & Witchger 2010). In the present study, we examine if smartphone and social media use affects tourists’ positive emotions, and if these effects are moderated by traveling alone or accompanied.

2 Literature Review

Three bodies of literature form the framework for the present study, wherein we address the shortcomings of all three in addressing the link between smartphone and social media use and tourists' emotions. First, the increasing influence of smartphone use and social media on tourism has been paralleled by a growing research interest in the topic. Research on tourists’ behavior in this reshaped technological landscape has focused on marketing and decision formation, while relatively little has explored tourists’ on-site experiences, and even less on emotions. Second, tourists’ experiences have repeatedly been studied in terms of emotions. Only a couple of tourist emotion studies addressed technology, however, and those focused on cameras rather than wireless connectivity and social media. Finally, several studies have addressed the experiential differences between solitary and accompanied tourism. These have also not addressed the present technological landscape.

Tourist use of smartphones and social media

The intertwined developments of wireless connectivity through smartphones and sharing of content on social media have profoundly impacted society over the past few years (Wang, Xiang, & Fesenmaier 2014). In this time a number of scholars have studied the impacts of wireless connectivity and social media on tourism, though theoretical explanations of technological impact on experiences are only now beginning to appear (Tussyadiah, Jung, & tom Dieck, 2018). Excellent literature reviews of tourists’ wireless connectivity through smartphones (Dickinson et al., 2014) and social media participation (Munar & Jacobsen, 2014) exist. Rather than duplicating these comprehensive efforts, we give a brief overview of this research and focus on the effects of these connected technologies on the tourist experience. Currently, "online tools, technologies and apps have already become integral parts of the travel industry and the typical consumer’s decision-making path” (Steinbrink, 2013, p. 3).

In the pre-travel phase of an individual's tourism experience, wireless connectivity and social media have transformed tourists’ information search and purchase behavior (Dickinson et al. 2014). Customers now demand precise, personalized, social information on the components of experiences they consider purchasing. According to Buhalis and Law (2008), being able to access unprecedented choice in tourism product and pricing information has made tourists more powerful and more selective as consumers. Smartphones and their constituent applications have accelerated these developments (Dickinson et al., 2014). Global Positioning System satellite receiver hardware in mobile phones and tablets have made it possible to integrate customers’ locations into their social and commercial interactions (Pedrana, 2014).

The supply of information available to tourists through wireless connectivity has been assessed (Dickinson et al., 2014) but impact on tourists’ emotions has not. Dickinson et al. propose, however, two positive effects that information via smartphone app may have on the tourist experience. First, the information reduces stress due to navigation and wayfinding. Second, the contextual awareness of apps reduces the need for planning and attending to clock time, possibly improving the feeling of "escape” from daily life. Empirical findings support the cognitive components of these propositions, showing that tourists have an easier time wayfinding and making spontaneous decisions, without clarifying how these changes make tourists feel emotionally (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the implication in Wang et al. (2016), and consistent with evidence from app reviews in Wang et al. (2012), is that smartphone use contributed to tourists' positive emotions. This theoretical assertion, that by addressing tourists’ functional needs during their experiences, wireless connectivity and its specific functionalities, including social media, contribute to positive emotions, forms a starting point for our study.

Wireless internet is often used to access social network sites like Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and YouTube to share experiences with other users (Munar & Jacobsen 2014). Furthermore, social media can be seen as a hybrid of traditional demand-supply communication and consumer-to-consumer information sharing (Kietzmann et al., 2011; Mangold & Faulds, 2009). Social media and online review platforms, which are similarly based on customers sharing their experiences, are now crucial to tourist decision making (Jacobsen & Munar, 2012; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Mangold & Faulds, 2009; Xiang & Gretzel, 2010). Developing interactive communication and invoking user engagement is easier with social media than with traditional media (Dijkmans, Kerkhof, & Beukenboom 2015; Hollebeek, Glynn, & Brodie, 2014). Because of its social, organic nature, "social media has become an increasingly trusted source for shaping brand perceptions” (Steinbrink, 2013, p. 3), where Fotis, Buhalis, and Rossides (2012, p. 14)found that "information from other travellers in various websites is trusted more than official tourism websites, and travel agents.” If a well-connected individual uploads reports of a negative travel experience to social media, it can quickly damage the reputation of a company or destination (Zhou & Wang, 2014). Access to information via the smartphone and the option to complain via social media makes tourists "far less willing to wait or put up with delays, to the point where patience is a disappearing virtue” (Buhalis and Law, 2008, p. 5).

The growth of social media has coincided with a growing urge among tourists to share their experiences with others. Shared information, photos, and videos are known as user-generated content (Jacobsen & Munar, 2012; Xiang & Gretzel, 2010). User-generated content refers to information that is digitized, uploaded by the users - often using a wireless connection - and made available over social media or review sites. Tourists photograph using smartphones and share and tag these photos on social media, often spreading awareness of a single tourist’s photo across hundreds of real and virtual relationships (Konijn, Sluimer, & Mitas 2016). In the past, word of mouth stayed within an individual’s (offline) social network, but current developments make it possible for consumers to expand the size of their social networks and make social communication more public than before (Morosan, 2013).

Existing research linking tourism and social media has focused on decision making, planning, and marketing opportunities rather than tourists’ experiences. Nevertheless, a few studies do suggest that social media influence the tourist experience. The cited studies of smartphone use by Wang and colleagues (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2016) highlight social media as a source of "fun” (Wang et al., 2014, p. 19) complementing the positive effects from other smartphone applications. Perhaps the most direct evidence comes from Wang et al.’s study of app reviews (2012), in which some social applications are celebrated as potential tools to "share happiness” (p. 380). Also, Hudson et al. (2015) found effects of social media use on positive emotions in the context of festivals. The theoretical assertion implied by these findings is that fulfillment of personal needs, especially for information and social connection, contribute to positive emotions tourists’ experiences. Unfortunately, this assertion has never been tested with data collected from tourists in situ. As for smartphone use, previous research suggests that tourists who use social media more have more positive emotions in their experiences. To put these hypotheses in a more complete theoretical context, it is necessary to briefly synthesize existing research on tourists’ emotions.

3 Tourists’ emotions

Tourists’ emotions are considered an important aspect of the tourist experience. Emotions influence satisfaction (del Bosque & San Martin, 2008; Lee et al., 2014; Song, Ahn, & Lee, 2013) and revisit intention (Prayag, Hosany, & Odeh, 2013; Hosany & Gilbert, 2010). Emotions can be used as a psychographic segmentation variable (Bigne & Andreu, 2004). Research on tourists’ emotions is considered crucial in the contemporary "emotion economy” in which people purchase based on their feelings, especially emotions they expect from the consumption experience (Rock, 2015).

In this study, we use the widely accepted psychological definition of emotions as brief, intense, complex responses to internal and external stimuli (Rosenberg, 1998). Emotions are triggered by meaningful events in the environment or thoughts of an individual. They arise quickly, occupy the foreground of consciousness, and predictably motivate decision-making and behavior (Fredrickson, 1998). Emotions fuel crucial mental processes such as deciding whether something is worth remembering or not, and deciding whether something is desirable or not. Beginning with Hammitt`’s (1980) test of Clawson and Knetsch’s classic recreation experience model (1966), previous research shows increases in positive emotions during tourism experiences (e.g., Mitas et al. 2012a; Strauss-Blasche, Ekmekcioglu, & Marktl 2000).

Several triggers of emotions in tourism experiences have been posited. An important mechanism of emotion is interaction between people (Farber & Hall 2007; Kang & Gretzel 2012; McCabe 2009; Nawijn, 2011; Mitas, Yarnal, & Chick, 2012b; Strauss-Blasche et al. 2005). A specific activity between travel companions as well as strangers that influences emotions is photographing (Gillet, Schmitz, & Mitas, 2016). Other variables related to emotions on holiday include holiday stress (Nawijn 2011), viewing scenery and wildlife (Farber & Hall 2007), weather (Jeuring & Peters, 2013), relaxation (Nawijn et al., 2010), and highly proximate cognitions such as goal congruence (Ma et al., 2013).

Several studies have also found differences among specific emotions, such as interest, warmth, amusement, and the sublime (Mitas, Yarnal, & Chick, 2012), joy, love, and positive surprise, (Prayag et al., 2013), excitement and pleasure (Farber & Hall, 2007), and delight (Ma et al., 2013). A broader study conducted a developmental breakdown of 19 emotions over the course of a vacation (Lin et al., 2014). In sum, research shows that tourists’ experiences are rich and varied in emotions, especially positive emotions (Hosany & Gilbert, 2010). We thus focus on positive emotions in particular in our study. The role of wireless connectivity in tourists’ emotions is understood only from the perspective of tourist photographing, however, leaving the more general effects of wireless connectivity on tourists’ positive emotions unknown. Given the importance of social interactions to tourists’ positive emotions, we posit that the effect of wireless connectivity on tourists’ positive emotions must be examined in light of whether tourists are traveling solo or accompanied.

4 Solo and accompanied tourists

The tourism research literature widely recognizes a difference in the experience of tourists who travel alone, and those who travel with one or more companions (e.g., March & Woodside, 2005; Lew & McKercher, 2006). Solitary travel has been recognized as being either by choice or by default (Mehmetoglu, Dann, & Larsen, 2001). Lack of a travel companion can be a reason to travel alone. Previous research has found that sharing experiences and memories is a motivation to travel with companions, and something that solo tourists miss (Mehmetoglu et al., 2001; Heimtun & Abelsen, 2012). Heimtun and Abelsen (2012) also found that solo tourists – especially women – have significant negative feelings towards eating out alone in tourism destinations. These findings suggest that solo tourists may have stronger needs for social contact. According to the established theory on tourists’ smartphone use, solo tourists may thus benefit more from smartphone use because it addresses a more urgent need for them. This notion has not been empirically tested, however.

These potentially negative aspects of traveling alone do not mean that solo tourists enjoy their experiences less. According to Mehmetoglu et al. (2001), solo tourists often demonstrate an inner desire to display autonomous and independent behavior. Additionally, it is notable that Mehmetoglu et al.'s participants did not see traveling solo or with companion as alternatives. Rather, individual travel was being seen as an experience in itself. Solitary travel can thus provide substantial benefits, especially for tourists with certain personalities. The conscious choice to travel solo is motivated by aspirations such as self-development and self-realization (Mehmetoglu, Dann, & Larsen, 2001). Often solo tourists see the constraints of traveling alone as challenges to be negotiated (Heimtun & Jordan, 2011). Also, enjoyment of traveling with companions depends substantially on relationships within the travel party (Mitas et al., 2012b; Nawijn, 2011).

In sum, the effects of traveling solo compared to accompanied travel on tourists’ experiences are complex and not fully understood. These effects are likely to interact with use of wireless connectivity. A potential theoretical explanation for this interaction can be found in literature about flashpacking, an emerging variant of backpacking tourism in which online information and social connections replace or complement in-person travel companions. Fifteen years ago, information gathering was the main motivation for backpackers to interact with one another (Murphy 2001). More recently, according to Molz and Paris (2013), there are signs that flashpacking increasingly describes the typical contemporary backpacker, rather than a niche backpacker subculture. These findings suggest that seeking information online through mobile connected technology may replace or reduce in-person interactions among tourists, which are known to affect their emotions (Mitas et al., 2012b; Nawijn 2011). Thus, the theoretical framework for the present study posits that tourists experience positive emotions because technology use fulfills their informational and social needs, and that use of social media may replace the in-person social needs of solo tourists in particular. A conclusive examination of this theoretical framework would be methodologically complex, requiring reporting on emotions and motivations combined with digital "snooping” on participants’ technology use, as well as physiological measures of emotion, which allow continuous, unobtrusive monitoring of emotional experience (Bastiaansen et al., 2019). We instead undertake an initial examination of this theory by testing the relationship between wireless connectivity and social media use and positive emotions, moderated by traveling alone or accompanied, using a self-response questionnaire in situ. Such an in-situ measurement of technology use and its impact on individual tourist experience comprises a novel contribution to the tourism literature.

5 Research questions

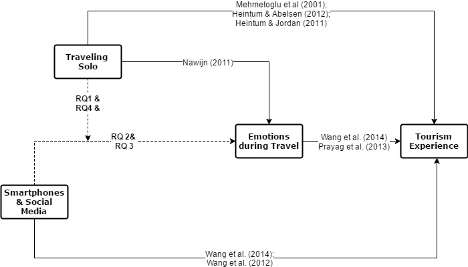

Tourists’ growing use of wireless connectivity and social media has a demonstrable effect on tourism experience. However, there is a lack of knowledge on the differential effects of wireless internet and social media use on solo and accompanied tourists’ positive emotions, which may arise from different social needs. Figure 1 encompasses a framework to illustrate these omissions. The main focus of the present paper will be the question: Does using wireless internet or social media affect the positive emotions of solo tourists differently than the positive emotions of accompanied tourists?

It is expected that wireless connectivity and social media use will show a positive relation with positive emotions for both types of travelers, but that this effect will be stronger in solo than in accompanied tourists, as their social needs are more salient than those of accompanied tourists, and social media in particular may be seen as a substitute for socializing in person.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

6 Methods

Data Collection

Data were collected using self-report questionnaires in Amsterdam. Sixteen student research teams were subdivided over tourist attractions in and near the city. These attractions were selected by the authors in cooperation with student research teams and included common sightseeing areas, such as the Dam Square and prominent intersections on the canal ring, as well as main shopping streets and queues for cultural tourism attractions such as the Anne Frank house and Museum Square. With this diversity in mind, we attempted to capture a broad, though not proportionally representative, sample of tourists to Amsterdam. The questionnaires were distributed to tourists using a systematic quota sampling approach. All research teams were briefed beforehand to distribute questionnaires systematically regardless of age, nationality, or group size.

A total of 766 tourists filled in the questionnaire during a three-day period in May 2015. The tourists surveyed originated from 75 different countries. The median age was 28 years old and 56.1% of the participants were female. Solo tourists comprised 15.3% of the total sample (n=117). Of the 766 questionnaires collected, 105 featured missing data, and were used for subsequent analysis only when the items analyzed were completed.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire assessed general characteristics of tourists, including nationality, age, length of stay, and whether or not they were traveling alone. Only those respondents that brought a mobile device on their trip (721, or 94.1% of the sample) answered subsequent questions. Respondents were asked to indicate the number of hours per day they were connected to wireless internet during their trip. Items adapted from de Reuver and Bouwman's (2015) valid and reliable scale on purposes for using wireless internet on mobile devices followed. For each purpose, respondents indicated on a 5-point Likert scale from very rarely to very often the extent to which they used wireless internet on their mobile devices for each purpose. The item measuring the purpose of "accessing social media” was used for subsequent analysis.

We measured emotions using the well-validated modified Differential Emotions Scale (Cohn et al. 2009), which we further modified and validated for relevance and clarity to participants based on previous research in this context (Konijn et al., 2015). Our scale comprised 18 different emotions, including 10 positive emotions and 8 negative emotions. For each emotion respondents were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all to extremely the extent to which they experienced this emotion during their trip. Only the data from the positive emotions were used for subsequent analysis, because the data from the negative emotion questions showed extremely negative skew (which is not uncommon, see e.g. Hosany & Gilbert, 2010; Richins, 1997) and our explicit theoretical choice was to focus on positive emotions, in line with numerous previous tourism studies (e.g., Hosany et al., 2016; Mitas et al., 2012). The positive emotions were: Interested, Positively Surprised, Amused, Loving, Awed, Proud, Joyous, Grateful, Hopeful and Content. Note that this list includes positive emotions of varying typical arousal levels, a main goal of Cohn et al.’s (2009) modification of the original Differential Emotions Scale.

Data analysis

Our analysis choices were guided by our theoretical framework, namely that social media and wireless internet use may influence positive emotions which are more salient among solo tourists. Although the cross-sectional design of our study rules out empirically testing for the direction of causation, this theoretical framework implies analyzing social media and wireless internet use as predictors of the outcome, positive emotions, with traveling solo or accompanied as a moderator of this relationship.

For each positive emotion, an independent-samples t-test was performed to assess differences between emotions experienced by solo tourists and those experienced by accompanied tourists. Where necessary, degrees of freedom were adjusted to accommodate for violations of the assumption of equal variances. Then, multiple regressions were conducted on subsamples of solo and accompanied tourists, with positive emotions (computed as the sum score of all 10 positive emotions) as the dependent variable and wireless internet and social media use as independent variables. Finally, two moderation analyses were performed, using the PROCESS plugin for SPSS (Hayes, 2015). In both analyses, positive emotions served as the dependent variable, and traveling alone as the moderator variable. For one analysis we used social media use as the independent variable, while for the other we used wireless internet use as the independent variable. In case of a significant interaction, a simple-slopes analysis was used to characterize the nature of the moderation effect.

Limitations

Choosing solely one destination during three consecutive days at a particular time of year affected external validity of the research. Although Amsterdam can be considered a hub of diverse tourists, it must be acknowledged that the current research set-up does not allow generalization beyond this time and geographical frame. While we measured positive emotions and social media use using scales previously tested for reliability and validity, our single-item measure of wireless connectivity was previously untested and is difficult to validate on its own, despite having face validity and low participant burden. Furthermore, where the present study appears to indicate that using social media contributes to a tourists’ emotions during travel, causality could not be implied. Conclusions are thus restricted to relation rather than causation.

7 Results

Experiences of solo and accompanied tourists

Table 1 shows that significant differences between positive emotions experienced by the two types of travelers were observed for the emotions of love, pride, and interest. Solo tourists experienced more pride, while accompanied tourists experienced more love and interest.

Table 1

T-test on emotion differences between types of tourists

Emotion | Mean (SD) Solo | Mean (SD) Accompanied | t | df | p |

Interested* | 4.13 (.912) | 4.30 (.706) | -2.337 | 738 | .020 |

Surprised | 3.88 (.943) | 3.91 (.834) | -.337 | 738 | .740 |

Amused | 3.76 (.952) | 3.18 (.968) | -.500 | 728 | .617 |

Loving** | 3.25 (1.035) | 3.73 (1.048) | -4.399 | 731 | <.001 |

Awed | 3.05 (1.182) | 3.08 (1.201) | -2.79 | 711 | .780 |

Proud* | 3.12 (1.245) | 2.86 (1.18) | 2.094 | 733 | .037 |

Joyous | 3.92 (.964) | 3.77 (0.985) | 1.479 | 729 | .140 |

Grateful | 3.81 (1.083) | 3.72 (1.091) | .820 | 731 | .412 |

Hopeful | 3.26 (1.088) | 3.29 (1.126) | -.257 | 734 | .797 |

Content | 3.90 (.953) | 3.88 (1.065) | 0.165 | 162.9 | 0.869 |

* p <0.05 ** p<0.001

Mobile internet and social media use within solo and accompanied subsamples

The multiple regression model within the solo tourist subsample predicted the positive emotions better than a model with no predictors (F2, 94 = 9.650, p < 0.001). Further, the model accounts for 17.0% of the variance in positive emotions for solo tourists. Accessing social media was a significant contributor in explaining positive emotions for solo tourists, while hours connected to wireless internet was not (Table 2).

Table 2

Parameters and test statistics for individual predictors of solo tourists’ emotions.

Predictor | Standardized ß | b | t | df | p |

Constant |

| 28.443 | 15.296 | 94 | < .001 |

Hours wireless internet | .115 | .020 | 1.209 | 94 | .230 |

Accessing Social Media | .376 | .200 | 3.994 | 94 | < .001 |

The multiple regression model within the accompanied tourist subsample predicted positive emotions better than a model with no predictors (F2, 558 = 3.517, p = 0.030). Unlike in the solo tourist subsample, for accompanied tourists the model accounted for only 1.2% of the variance in positive emotions. Accessing social media was a significant contributor in explaining positive emotions for accompanied tourists, while hours connected to wireless internet was not (see Table 3).

Table 3

Parameters and test statistics for individual predictors of accompanied tourists’ emotions.

Predictor | Standardized ß | b | t | df | p |

Constant |

| 34.944 | 53.684 | 558 | < .001 |

Hours wireless internet | -.004 | .000 | -.096 | 558 | .923 |

Accessing Social Media | .112 | .048 | 2.621 | 558 | .009 |

Interaction between solo/accompanied travel and technology use

The first moderation analysis, with accessing social media as the independent variable, revealed a significant interaction effect (b = -1.6299, t = -2.5281, p = .0117), indicating that traveling accompanied compared to traveling alone moderated the effect of social media use on positive emotions. A simple-slopes analysis further showed that the relationship between relative social media use and positive emotions was positive for solo tourists and attenuated, though still positive, for accompanied tourists (Figure 2). The second moderation analysis, with hours connected to wireless internet as the independent variable, did not show a moderation effect (interaction effect: b= -.3234, t = -1.4063 p = 0.1601).

Figure 2.

Simple-slopes analysis for the moderation effect of traveling party on the relationship between accessing social media and experiencing positive emotions.

8 Discussion

Summary of findings

Solo and accompanied tourists’ positive emotions.

We found a significant difference between solo and accompanied tourists’ experiences of three out of ten positive emotions: interested, loving, and proud. Solo tourists reported a higher level of pride, while accompanied tourists reported more intense love and interest. Cohen’s (1972) typology may partly explain the proud feeling of solo tourists. The self-expressive, exploratory, and challenging aspects of solo travel may create feelings of pride (Carter & Gilovich, 2012). Accompanied tourists’ higher scores for love can be explained by the fact that these tourists often have family members in their travel party. This phenomenon extends beyond family to include communities of repeat tourists, that is, social groups which form by repeatedly engaging in an annual organized group tourism experience (Mitas, Yarnal, & Chick, 2012; Yarnal & Kerstetter, 2005). Solo tourists miss out on such experiences by traveling alone and thus may experience less of this specific positive emotion. Both accompanied and solo tourists scored relatively high on interest, but accompanied tourists scored even higher than solo tourists. Sharing knowledge about a specific attraction or feature of a destination with those present may increase the feeling of being interested, as was observed in special interest tour groups by Mitas et al. (2012).

The effects of smartphone and social media use on tourists’ positive emotions.

The literature suggested that smartphone and social media use may both contribute to tourists’ positive emotions by fulfilling their informational and social needs (Dickinson et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). As solo tourists experience a different social context in which they are not consistently accompanied, their social needs may be greater, leading to greater emotional benefit from using social media in particular. The multiple regression analysis showed that social media use was positively related to positive emotions. The standardized ß-value of .375 suggested a medium to high effect size and the overall model explained for 17.0% of the variance in positive emotions. It is important to note here that the goal of this model was not to explain all sources of tourists’ positive emotions, in which case 17% would be a rather low proportion. Rather, the goal of the model was to elucidate the effect of social media use to positive emotions. Under this approach, 17% is a substantial proportion, considering the myriad experiential variables that may affect positive emotions.

For accompanied tourists, social media use was also positively related to positive emotions, but the model explained only 1.2% of the variance in positive emotions, which is notably lower than the model for solo tourists. Social media use had a standardized ß-value of .112, which comprises a small effect. More time connected to wireless internet did not affect positive emotions of either solo or accompanied tourists.

The effect of traveling solo or accompanied on the technology–emotion relationship.

Moderation analysis confirmed that the positive relationship between social media use and positive emotions was significantly strengthened by traveling alone. Simple slopes analysis showed that the effect of using social media on positive emotions was more powerful for solo tourists than for accompanied tourists. In other words, when tourists access social media relatively little, accompanied tourists experience more positive emotions than solo tourists, but as participants increased their frequency of accessing social media, the solo tourists begin to experience more positive emotions than accompanied tourists.

Contributions to literature

Our findings extend knowledge on technology use in tourists’ experiences in three ways. First, our findings are consistent with the theory that technology can have a positive effect on tourists’ experiences, and we uncovered the magnitude of this effect. Second, we specify that these positive effects occur with social media use, but not with wireless connectivity in general, suggesting that the positive effects of technology may be more social than informational, although further research focused on these specific purposes is needed. This finding is congruent with previous research on tourist photographing, but not with the emphasis on information in previous research on tourists’ technology use. Third, we show that this effect is accentuated for tourists who travel alone, suggesting that controlling one’s social environment may partly account for the benefits of traveling alone mentioned in previous literature, and once again stressing that mobile technology appears to fill more social than informational needs.

Several previous studies based on app reviews (Wang et al., 2012) as well as interviews (Wang et al., 2016) suggested that social media and wireless internet use may positively affect tourists’ emotions by addressing tourists’ social and informational needs. Our findings confirm that such an effect exists for social media use. Tourists in our sample who used social media experienced higher levels of positive emotions. Key to our contribution was our approach of measuring social media and wireless internet use, and testing the effects of these on a specific, valid, and reliable measure of tourist experience outcomes, namely positive emotions. This approach makes it possible to conclude with more confidence that the current proliferation of mobile connected devices in tourist experiences contributes to positive emotions, as has been argued (Dickinson et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2016).

The argument from literature that the positive effects of wireless connectivity on tourists’ experiences are due to the ease of finding useful information may be inaccurate, however. If information made the tourists in our sample feel good, we would expect time spent on wireless internet, but not necessarily social media use, to predict positive emotions. In fact, we found the opposite, that social media use but not time spent on wireless internet predicted positive emotions. This finding is consistent with recent research that linked photographing with positive emotions, showing that it is largely social interaction and (offline and online) sharing that makes photographing enjoyable (Gillet et al., 2016; Konijn et al., 2016). The positive effects of social media we found may in fact partly be driven by the sharing of photographs. The studies of Gillet et al. (2016) and Konijn et al. (2016) were among the first to link technology use measures to valid and reliable emotion experience scales, but their findings were limited to photographing.

Our findings extend the role of social interaction in creating positive emotions to tourists’ technology use more generally, as social media facilitate social interaction (Büscher et al., 2010), whereas wireless connectivity facilitates not only social interaction but also information search, navigation, and e-commerce. As time spent on wireless internet did not affect our participants’ positive emotions, the argument that smoother information search and easier navigation contributes to tourists' positive emotions (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016) should be questioned. It seems more likely that the benefits of information and navigation are cognitive, and the benefits of social interaction, offline as well as over social media, are emotional. Indeed, the importance of social interactions for tourists’ positive emotions is also tangible in face-to-face interactions (Mitas et al., 2012). It is also possible that the informational benefits of smartphone use come largely through social media, which contains an increasing volume of information that is useful for tourists. Thus, the possibility that tourists’ emotional benefit from social media use comes primarily from meeting informational needs also deserves further investigation.

The effect of social media use on positive emotions was much stronger for solo tourists, who were also found to experience more pride and less interest and love. This moderation effect recalls the ambiguous nature of solo travel––while it is often not by choice (Mehmetoglu et al., 2001) and may feel lonely (Heimtun & Abelsen, 2012), it also presents opportunities to express the self (Mehmetoglu et al., 2001) and to control one’s own itinerary. On social media, solo tourists make the best of their situation, expressing their pride with attractively filtered photos and cleverly-placed selfies, conversing with distant family and strangers, and "checking in” at whatever moment they find convenient (Paris, 2012). The social contact in social media may make solo tourists feel less lonely, an example of how wireless connectivity contributes to positive emotions by fulfilling social needs. Ethnographic research that would record and interpret wireless internet use could further elucidate this process.

Furthermore, Wang et al. (2012) found that filling downtime is one of the main benefits of wireless connectivity, and one can easily imagine that downtime is often filled with scrolling through Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram feeds. This may imply a third need, besides social and informational, that technology fulfills for tourists: an entertainment need. The extent to which tourists seek stimulation from technology simply for entertainment merits further research, perhaps from the perspective of optimal arousal theory.

A further possible explanation for the finding that solo tourists experience a stronger effect of social media use on their positive emotions is that traveling alone affords tourists a degree of control over their social environment. They are free to make their own itineraries and seek solitude, yet social media allows them similar freedom in choosing to when connect with others, and with whom. While accompanied tourists experience positive emotions from interactions with their travel party (Mitas et al., 2012b), they have relatively less choice in who they interact with and when, as their travel companions often remain largely the same over their entire experience. Their itineraries may be less flexible as well. The freedom gained by traveling alone, along with the easily controlled if limited social contact over social media, gives solo tourists control over their social environment. We found that when they elect to use this control to connect with others over social media relatively more frequently, solo tourists gain appreciably in their positive emotions, a novel finding in the literature. To further explore solo tourists’ perception and use of the increasing control that technology affords them, research based on interviewing or observing these tourists in situ is warranted.

9 Recommendations for the tourism industry

The importance of wireless connectivity and accessing social media, especially in the case of solo tourists, indicate the importance of wireless internet infrastructure and interaction. Promoting social media use by, for example, setting up a free Wi-Fi hotspot with a fixed start page – the social media page of an attraction - may have a two-sided effect. Firstly, it tends to prompt likes, shares, and comments and thus the promotion of the page, and secondly it might enhance the positive emotions of these tourists.

The moderation effect of traveling alone or accompanied can indicate a need for more segmentation in between those types of tourists. Destinations may utilize, for instance, social media communities for backpackers or solo tourists to address this specific group or to promote sharing experiences during their trip by tourists on these communities. Also, tourism organizations should think critically about their approach to interacting with customers on social media, as many only send content in a one-way fashion while failing to respond to direct messages and comments (Vinkesteijn, 2017). Considering that social media use appears to trigger positive emotions in tourists, it is worth exploring if social media content and interactions originating from tourism organizations play a role in this effect.

10 Future directions

The finding of the moderation effect of traveling alone or accompanied on the relationship between social media use and positive emotions suggests opportunities for future research to delve deeper into the role of travel companions––or lack thereof––in tourists’ experiences. Additionally, it could be interesting to analyze the specific behaviors within social media use, whether it is posting pictures, chatting with friends or finding information, that influences tourists’ positive emotions most. Such variables could be added to the present model within a moderated mediation path analysis framework. Also, we recommend for future research to explore which aspects of social interactions affect tourists’ emotions, and how these interactions affect emotions.

Future studies should document levels of wireless connectivity and social media use by individual differences such as age, gender, and nationality. Furthermore, the effects of wireless connectivity and social media use may differ for tourists of different personalities and cultural backgrounds. A more refined understanding of social processes in the tourist experience, including online interactions facilitated by mobile wireless connectivity, promises opportunities for the tourism industry to further enhance the quality of their customers’ experiences.

We would like to thank Sebastiaan Straatman for his assistance in collecting the study data, and Corné Dijkmans for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

Bigne, J. E., & Andreu, L. (2004.) Emotions in segmentation: An empirical study. Annals of Tourism Research, 31, 682-696.

Büscher, M., Urry, J., & Witchger, K. (eds.). (2010). Mobile methods. London: Routledge.

Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 294, 609-623.

Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2012). I am what I do, not what I have: The differential centrality of experiential and material purchases to the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1304-1317.

Clawson, M., & Knetsch, J. L. (1966). Economics of outdoor recreation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cohen, E. (1972). Toward a sociology of international tourism. Social Research, 39, 164-182.

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9, 361-368.

Curtis, S. (2014). Quarter of the world will be using smartphones in 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/mobile-phones/11287659/Quarter-of-the-world-will-be-using-smartphones-in-2016.html (Accessed December 11, 2014).

de Reuver, M., & Bouwman, H. (2015). Dealing with self-report bias in mobile Internet acceptance and usage studies. Information & Management, 52, 287-294.

del Bosque, I. R., & San Martín, H. (2008). Tourist satisfaction a cognitive-affective model. Annals of Tourism Research, 35, 551-573.

Dickinson, J. E., Ghali, K., Cherrett, T., Speed, C., Davies, N., & Norgate, S. (2014). Tourism and the smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Current Issues in Tourism, 171, 84-101.

Dijkmans, C., Kerkhof, P., & Beukeboom, C. J. (2015). A stage to engage: Social media use and corporate reputation. Tourism Management, 47, 58-67.

Farber, M. E., & Hall, T. E. (2007). Emotion and environment: Visitors' extraordinary experiences along the Dalton Highway in Alaska. Journal of Leisure Research, 39, 248-270.

Fotis, J., D. Buhalis, & N. Rossides, N. (2012). "Social media use and impact during the holiday planning process.” In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2012: Proceedings of the International Conference in Helsingborg, Sweden, January 25-27, edited by M. Fuchs, F. Ricci, and L. Cantoni. Vienna: Springer.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology,2, 300-319.

Gillet, S., Schmitz, P., & Mitas, O. (2016). The snap-happy tourist: The effects of photographing behavior on tourists’ happiness. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40, 37-57.

Hammitt, W. E. (1980). Outdoor recreation: Is it a multi-phase experience? Journal of Leisure Research, 12, 107-115.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. Retrieved from www.processmacro.org.

Heimtun, B., & Abelsen, B. (2012). The tourist experience and bonding. Current Issues in Tourism, 155, 425-439.

Heimtun, B., & Jordan, F. (2011). ‘Wish YOU Weren’t Here!’: Interpersonal Conflicts and the Touristic Experiences of Norwegian and British Women Travelling with Friends. Tourist Studies, 113, 271-290.

Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 282, 149–165.

Hosany, S., & Gilbert, D. (2010). Measuring tourists' emotional experiences toward hedonic holiday destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 49, 513-526. doi:10.1177/0047287509349267.

Hosany, S., Prayag, G., Deesilatham, S., Cauševic, S., & Odeh, K. (2015). Measuring tourists’ emotional experiences: Further validation of the destination emotion scale. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 482-495.

Hudson, S., Roth, M. S., Madden, T. J., & Hudson, R. (2015). The effects of social media on emotions, brand relationship quality, and word of mouth: An empirical study of music festival attendees. Tourism Management, 47, 68–76. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.001.

Jacobsen, J. K. S., & Munar, A. M. (2012). Tourist information search and destination choice in a digital age. Tourism Management Perspectives, 1, 39-47.

Jeuring, J. H. G., & Peters, K. B. M. (2013). The influence of the weather on tourist experiences: Analysing travel blog narratives. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 19, 209-219.

Kang, M., & Gretzel, U. (2012). Effects of podcast tours on tourist experiences in a national park. Tourism Management, 33, 440-455.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 531, 59-68.

Kemp, S., Burt, C. D. B., & Furneaux, L. (2008). A test of the peak-end rule with extended autobiographical events. Memory & Cognition, 36, 132-138.

Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., & Silvestre, B. S. (2011). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons, 543, 241–251. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005.

Konijn, E., Sluimer, N., & Mitas, O. (2016). "Click to share: Patterns in tourist photography and sharing." International Journal of Tourism Research 18:525-535. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2069.

Lee, S. A., Manthiou, A., Jeong, M., Tang, L. R., & Chiang, L. L. (2014). Does Consumers' Feeling Affect Their Quality of Life? Roles of Consumption Emotion and Its Consequences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17,409-416.

Lew, A., & McKercher, B. (2006). Modeling tourist movements: A local destination analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 33, 403-423.

Lin, Y., Kerstetter, D., Nawijn, J., & Mitas, O. (2014). Changes in emotions and their interactions with personality in a vacation context. Tourism Management, 40, 416-424.

Ma, J., Gao, J., Scott, N., & Ding, P. (2013). Customer delight from theme park experiences: The antecedents of delight based on cognitive appraisal theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 359-381.

Mangold, W.G., & Faulds, D. J. (2009). Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Business Horizons, 524, 357–365. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.03.002.

March, R., & Woodside, A. G. (2005). Testing theory of planned versus realized tourism behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 32, 905-924.

McCabe, S. (2009). Who needs a holiday? Evaluating social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36, 667-688.

Mehmetoglu, M., Dann, G. M., and Larsen, S. (2001). Solitary travellers in the Norwegian Lofoten Islands: Why do people travel on their own? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11, 19-37.

Mitas, O., Nawijn, J., & Jongsma, B. (2017). Between tourists: Tourism and Happiness. In The Routledge Handbook of Health Tourism, Smith, M. K., & Puczko, L. (eds)., London: Routledge.

Mitas, O., Qian, X. L., Yarnal, C. M., & Kerstetter, D. (2011). ‘The Fun Begins Now!’: Broadening and Building Processes in Red Hat Society® Participation. Journal of Leisure Research, 43, 30-50.

Mitas, O., Yarnal, C. M., Adams, R., & Ram, N. (2012a). Taking a "peak” at leisure travelers’ positive emotions. Leisure Sciences, 34, 115-135.

Mitas, O., Yarnal, C. M., & Chick, G. (2012b). Jokes build community: Mature tourists’ positive emotions. Annals of Tourism Research, 394, 1884-1905.

Molz, G. J., & Paris, C. M. (2013). The social affordances of flashpacking: Exploring the mobility nexus of travel and communication. Mobilities, 10, 137-192.

Morosan, C. (2013). The Impact of the Destination's Online Initiatives on Word of Mouth. Tourism Analysis, 18, 415-428.

Munar, A. M., & Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2014). "Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media.” Tourism Management 43:46-54.

Murphy, L. (2001). Exploring social interactions of backpackers. Annals of Tourism Research, 281, 50-67.

Nawijn, J. (2011). Determinants of daily happiness on vacation. Journal of Travel Research, 50, 559-566.

Nawijn, J. & Fricke M.-C. (2015). Visitor emotions and behavioral intentions: The case of concentration camp memorial Neuengamme. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17, 221-228.

Nawijn, J., Marchand, M. A., Veenhoven, R., and Vingerhoets, A. J. (2010). Vacationers happier, but most not happier after a holiday. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 5, 35-47.

Paris, C. M. (2012). Flashpackers: An emerging sub-culture?. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 1094-1115.

Pedrana, M. (2014). Location-based services and tourism: Possible implications for destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 17, 753-762.

Prayag, G., Hosany, S., & Odeh, K. (2013). The role of tourists' emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 22, 118-127.

Richins, M. L. (1997). Measuring Emotions in the Consumption Experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 242, 127-146.

Rock, M. (2015). Human emotion: The one thing the internet can't buy. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/14/t-magazine/human-emotion-the-one-thing-the-internet-cant-buy.html?_r=0 (Accessed October 17, 2015).

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). "Levels of analysis and the organization of affect.” Review of General Psychology, 2, 247-270.

Song, H. J., Ahn, Y. J., & Lee, C. K. (2015). Structural relationships among strategic experiential modules, emotion and satisfaction at the Expo 2012 Yeosu Korea. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(3), 239-248. DOI: 10.1002/jtr.1981.

Steinbrink, S. (2013). Digital technologies in travel: Light at the end of the funnel? Now York: PhoCusWright.

Strauss-Blasche, G., Ekmekcioglu C., & Marktl, W. (2000). Does vacation enable recuperation? Changes in well-being associated with time away from work. Occupational Medicine, 50, 167-172.

Strauss?Blasche, G., Reithofer, B., Schobersberger, W., Ekmekcioglu, C., and Marktl, W. (2005). Effect of vacation on health: moderating factors of vacation outcome. Journal of Travel Medicine, 12, 94-101.

Tussyadiah, I. P. (2014). Toward a theoretical foundation for experience design in tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 53(5), 543-564. DOI: 10.1177/0047287513513172.

Tussyadiah, I. P., Jung, T. H., & tom Dieck, M. C. (2018). Embodiment of wearable augmented reality technology in tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 57(5), 597-611. DOI: 10.1177/0047287517709090.

Vinkesteijn, J. A. M. (2017). Hoe reageren toeristische bedrijven op Instagram vragen? travelnext.nl.

Wang, D., Park, S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2012). The role of smartphones in mediating the touristic experience. Journal of Travel Research, 514, 371-387.

Wang, D., Xiang, Z. & Fesenmaier, D.R., (2014). Adapting to the mobile world: A model of smartphone use. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 11-26.

Wang, D., Xiang, Z. & Fesenmaier, D.R., (2016). Smartphone Use in Everyday Life and Travel. Journal of Travel Research, 55, 52-63.

Xiang, Z., & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31,179-188.

Yarnal, C. M., & Kerstetter, D. (2005). Casting off: An exploration of cruise ship space, group tour behavior, and social interaction. Journal of travel Research, 43(4), 368-379.

Zhou, L., & Wang, T. (2014). Social media: A new vehicle for city marketing in China. Cities, 37, 27-32.

Contact-information

Ondrej Mitas

Senior Lecturer, Academy for Tourism, Breda University of Applied Sciences

Mgr. Hopmansstraat 14817 JT, Breda, Netherlands

+31 655 877 189