Nuffic grants everyone an enriching experience at international level

The art of balancing cross-border challenges

The Uncover editors talked to Lem van Eupen of Nuffic, the Dutch association for internationalisation in education. Lem is manager of the Europe pillar (Nuffic is organised in three pillars: Global, Europe, Netherlands), director of the Dutch National Agencies Erasmus+ and acting director at Nuffic.

Peter Horsten and Simon de Wijs work as lecturers and researchers at the Academy for Leisure & Events (BUas).

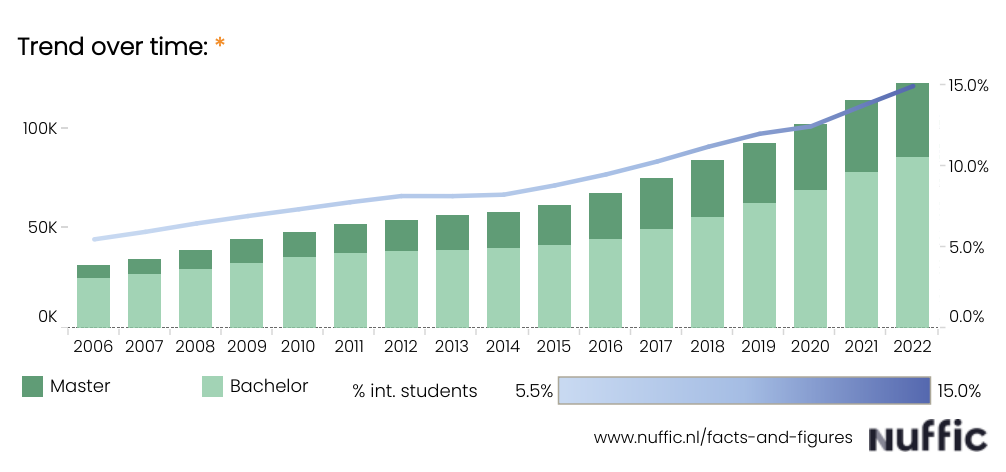

Nuffic was founded to promote international exchange and cooperation for primary and secondary education, mbo, hbo, wo, and adult education. Today, preschool nurseries have even been added for Erasmus+. Nuffic has several forms of services and activities. It runs big subsidy programmes on behalf of the Dutch Government and the European Committee, with which they give financial support to exchanges and cooperation. Think of Erasmus+ or the Orange Knowledge Programme for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In addition to the financial side, Nuffic also supports networks of internationally operating schools at various levels. What’s more, research is conducted into the impact of international exchange and cooperation. Nuffic has an online dashboard where you can interactively view research data. In this way, they support both government and education with data and analyses.

The context around internationalisation is always shifting, certainly now. What are the key priorities that Nuffic sets for the coming period?

We are developing the new Nuffic strategy for 2025-2030. An important key priority will be inclusive internationalisation. We believe that gaining international experience is not for the happy few, but that access to it should be as wide as possible. Especially for groups with very few opportunities, this opportunity means so much more than, say, university students who already go on holiday abroad with their parents twice a year anyway. We want to offer these valuable experiences to, for example, first-generation students and students with an immigration background who have difficulty accessing work placements - or are even discriminated against in this respect. There are wonderful inspirational stories on the Erasmus+ website (www.erasmusplus.nl/inspiratie-resultaten) and Nuffic has a network of WilWeg ambassadors (www.nuffic.nl/opnderwerpen/wilweg). We deliberately recruit first-generation students for this as well because they have a very difficult time in a higher education institute anyway. If you are the first in your family to study in higher education, you do not know the codes, you do not have the connections. A study abroad experience is even more complicated in that case. Then the people around you often do not understand why you want it.

Another key priority is digitisation. Physical mobility always remains very valuable because you also really enter a different world and are taken out of your comfort zone for a while. But there are increasing opportunities for remote collaboration and exchange thanks to new technologies. We are looking at how digitisation can best be used to exploit opportunities. This is always done in relation to that inclusive ambition. Especially since, during the Covid pandemic, we saw that digitisation carries the risk of a new divide. Some students did fine, some even better (because they sat quietly at home instead of in a busy school environment), but a very large proportion of students (from primary school to higher education) really fell behind and also suffered a mental dent during that time of limited physical contact. The human factor should not be lost sight of. As Nuffic, we try to find that balance.

We think gaining international experience is not for the happy few, but for everyone.

For Nuffic, how do digitisation and opportunities for hybrid education relate to issues of sustainability and travel?

Sustainability is a key focus. If you are honest, internationalisation is not necessarily about making the world greener because often physical travel is part of it, and that of course damages the climate. We do try to encourage sustainable travel. Erasmus+ launched the option of getting a top-up for 'green travel'. From this year (2024) it has even been reversed, making sustainable travel the norm. If you do not travel green, you will get a smaller allowance.

We as Nuffic, however, emphasise another aspect of internationalisation in relation with sustainability. Global problems, such as climate change, cannot be solved within national borders, and can only be addressed in an international context. That means international cooperation is crucial. Fortunately, many projects are submitted to Erasmus+ at present that deal specifically with sustainability in terms of content, such as urban mobility, greening transport, or forms of energy transition. Ultimately, a balance is needed between both the negative and positive aspects.

Why is it important to gain international experience?

We live in a world where national borders exist on the one hand, but where very important developments (e.g. climate, economy, trade) do not care about these borders. Through international experiences we get to know a world that is different and that broadens our view. Realising that one's own context is not the logical context for everyone, and that what we think is normal here is not normal for the whole world is essential for developing oneself personally and professionally. That young people return after an exchange with so much more confidence, self-reliance and an updated frame of reference allowing them to think more broadly than before is very valuable at all levels.

We recently published a study in which students returning from an Erasmus+ international experience were questioned five years afterwards about whether they have any lasting impressions. Professionally, 75% of individuals still perceive a difference, and on a personal level that percentage increases to over 90%. High percentages, which are also not surprising. Anyone with experience abroad will agree that being in a different context for a long time changes you permanently.

Is this thought under pressure given politics or countries focusing more on themselves and turning inwards?

The thought is not under pressure. Among young people, the enthusiasm for travelling and looking across borders has not changed a bit. Indeed, after the Covid pandemic, we saw Erasmus+ applications soar, and we are now above pre-Covid levels. On the other hand, you do hear from international students in the Netherlands itself that they feel less welcome. Not even so much within educational institutes themselves. Of course, there are some examples of Dutch students stating that they would be happy if the international students were gone, so there would be more space in lecture halls. Surely, not feeling welcome mainly plays a part in the environment outside the education institute. At the political level, the whole idea of international cooperation and exchange does come under considerable pressure.

At a political level, the thought of international cooperation and exchange is under much pressure.

Language plays a part in it. International students say, despite the fact that English is widely spoken in their studies, it is not easy for them to make contact outside their studies. What is your policy in this?

We do not have an active role in it because that is up to the institutes themselves. But it is clear that during an international experience, learning languages and being able to get by in that language enriches incoming and outbound and outgoing students. Thus, language also helps in becoming more widely involved and embedded in your Dutch environment tremendously. That applies during their studies but also for the likelihood of staying afterwards. Unfortunately, not everyone gets that chance by a long way. Look at stories of student flats, where people prefer not to opt for an international student. And Dutch lessons in a language lab will not get you there either. You need to have contacts and be able to build friendships with Dutch students. You also often see 'international communities' where internationals bond together rather than with locals. Many student associations do not always look at it specifically either. As an education institute you could facilitate or draw attention to this more. If you let people come here to study, you also have a responsibility for their well-being. This holds for all students, but even more so for internationals.

Getting back to digitisation. There is also the development of translation apps and AI. I am wondering what this will mean for the importance of learning another language. When you have a mobile at hand, you can just speak your own language, which can be read directly into the other language via an app. Language barriers are getting smaller, but learning a language is also immersing yourself in another culture while learning that language, and that will fall away (for the most part). Developments in this area may be faster than we can imagine.

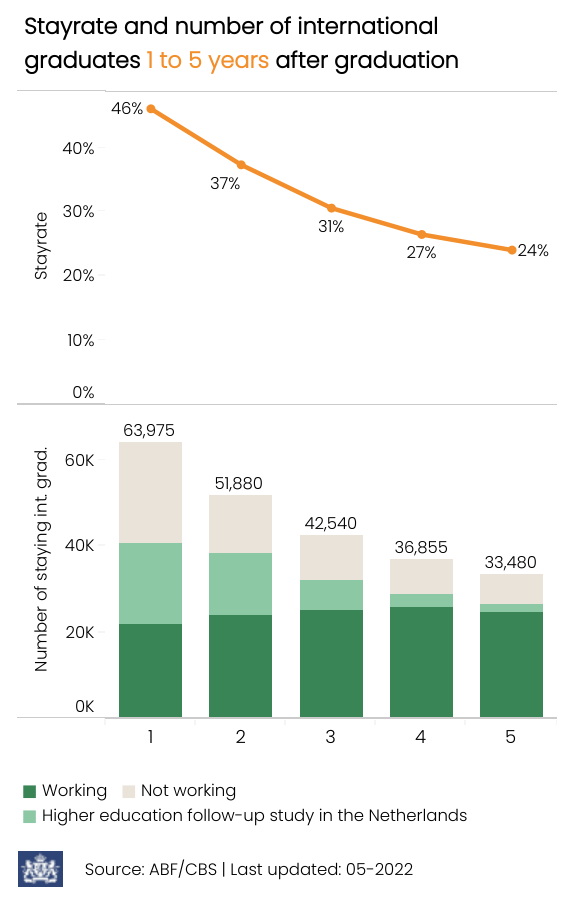

Is increasing the likelihood of staying after their studies a role for education institutes and is it a one-size-fits-all approach?

There are a number of shortage sectors with a lack of sufficient skilled workers where efforts are not only focused on bringing students here but also retaining them for the Dutch labour market. For example, ASML works closely together with Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e), where they get a significant share of their new employees. Government, education (much broader than TU/e, starting as early as in primary and secondary education) and businesses arrive at joint actions to look at what educational needs there are in the region and what this means for those entering the labour market. These regional approaches are very important to focus on increasing the likelihood of staying and contributing to the economy, innovation, and society.

By the way, there is absolutely no one-size-fits-all approach. Every higher education institute is autonomous and is allowed to make its own choices and there are many differences between regions and between disciplines. That sometimes means that every institute tries to maximise student numbers for themselves, which causes certain regions to get into trouble, and so you have to deal with it as a government. Limburg and Gelderland have a different approach to this than the provinces of Noord-Holland and Zuid-Holland. Partnerships between education, government and business are necessary to establish effective policies.

The Eindhoven example is often referred to, but what about healthcare education and the (future) dire shortage of hands on the bedside, for example?

I think there is still limited focused thinking about this kind of thing. Sometimes there is an initiative to bring a group of Indonesian or Filipino nurses to the Netherlands, train them using a pressure cooker formula, and then deploy them in healthcare. Too often these are ad hoc initiatives in which the entire ecosystem and preconditions are insufficiently mapped out. For instance, if you are dealing with people who need care, then language is a very important element. And that's where things go wrong in the above example. Beyond the figures, one must consider all those things in establishing the extent to which it is feasible to address existing labour needs using an international workforce.

Do you see any factors that education institutes can use to make choices regarding their internationalisation strategy and approach?

Nuffic is by no means saying that "as many students as possible should come to the Netherlands". While an institute can try to recruit individuals at a fair abroad, the question is whether that is wise and whether the numbers can be handled. At its core, it is always about what added value there is. An international approach is very logical for some institutes and study programmes, e.g. for the arts. Even for agribusiness or leisure & hospitality, for example, it is super logical to have international components in the programmes. By the way, that's not just about international students going back and forth. There are so many more forms to insert international components into study programmes.

Individually and collectively, educational institutes should think more about what and how many students we actually want to attract here. Including the questions of who can stay and who should certainly not be involved. Just studying here on a temporary basis is not the point then. It is also about the step afterwards. In that battle, by the way, you should not want to empty the ponds in other countries (brain drain). Here, too, it is always a matter of finding the right balance. Not everyone has to stay here to contribute to innovation and the economy. Some can also return to their own country and use the knowledge and experience gained to make a (significant) contribution there.

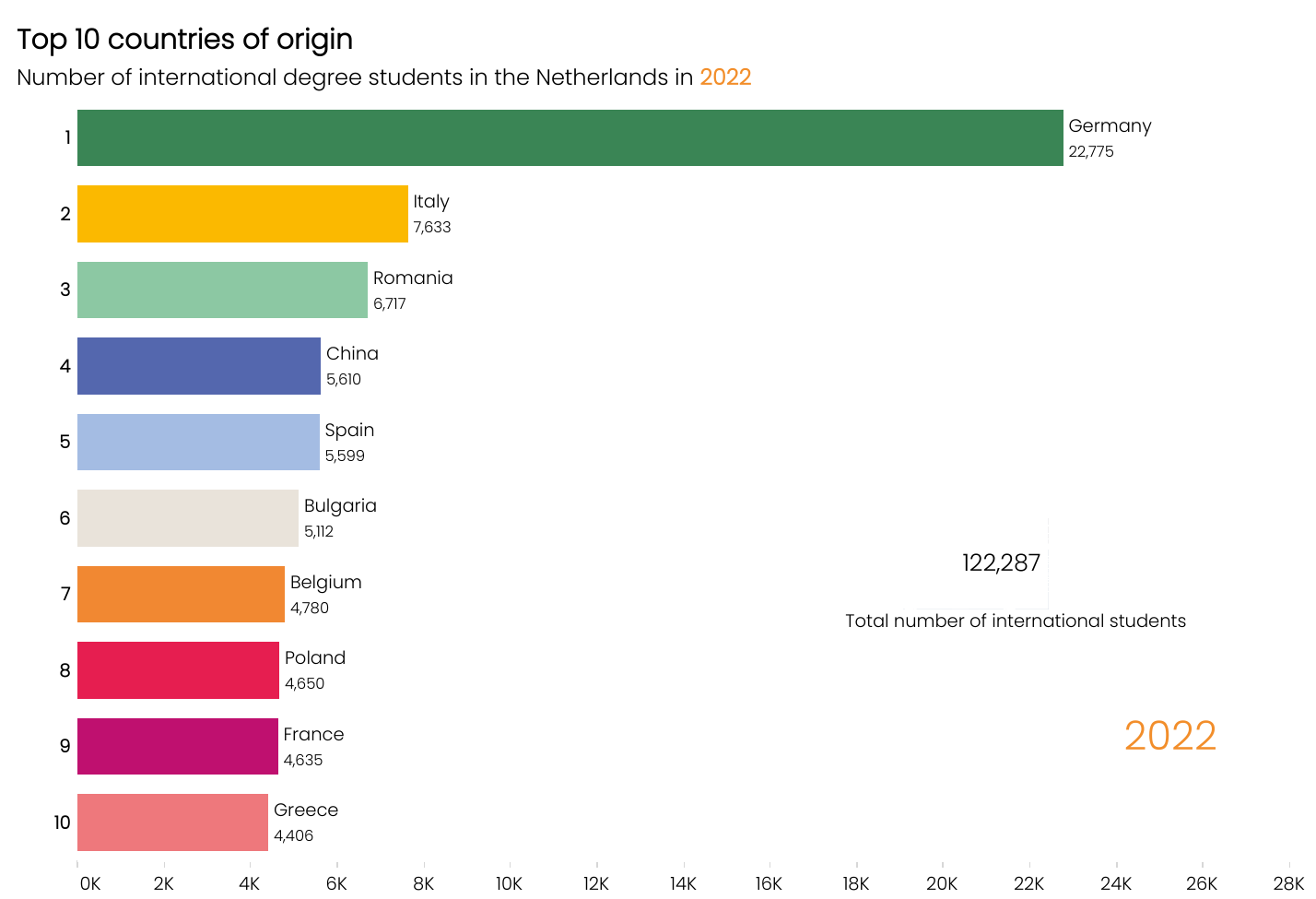

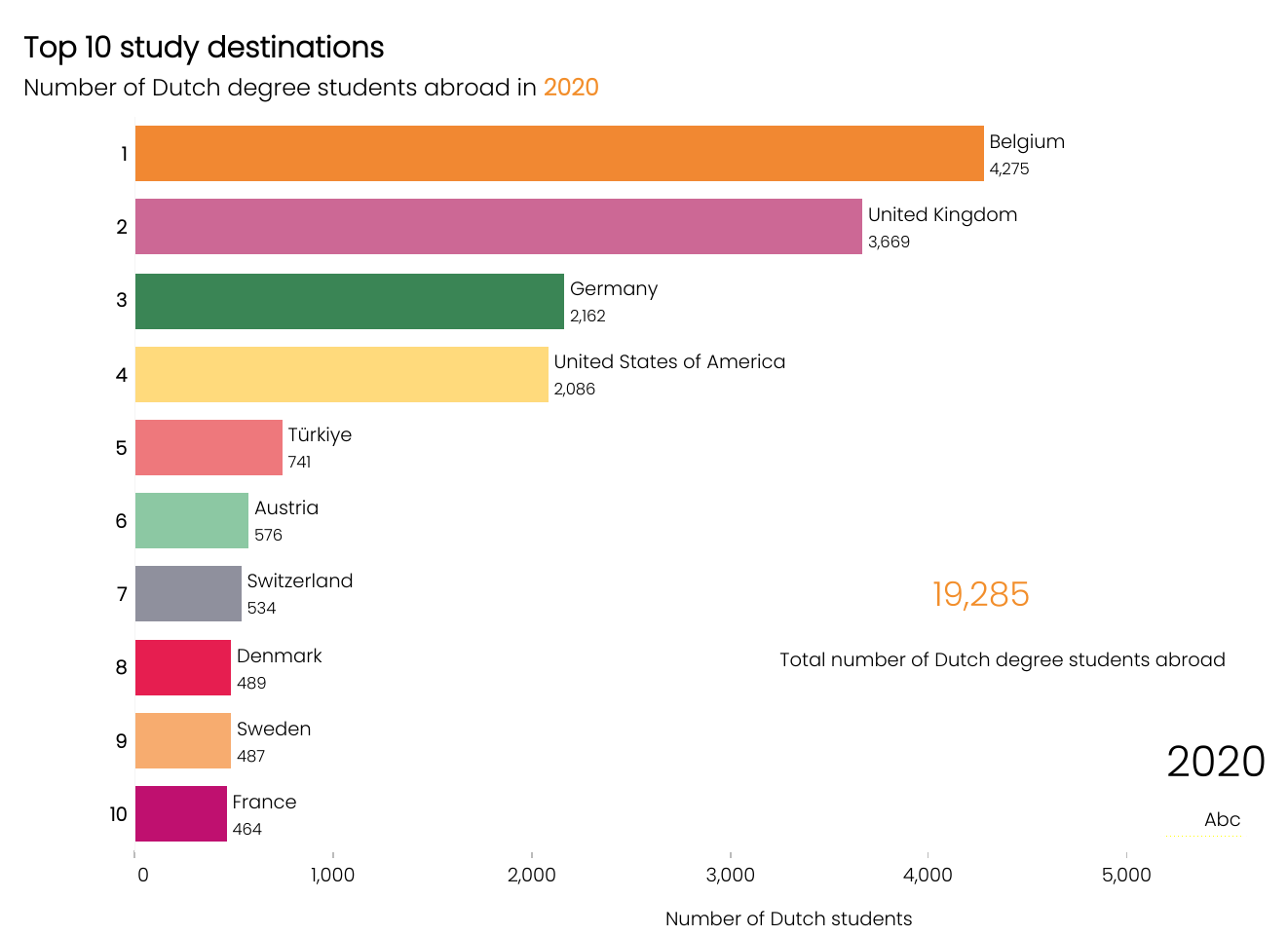

In the context of balance, explicitly promoting outgoing mobility is also very important since it is considerably lower than incoming mobility. In Erasmus+ it is almost balanced, but if you look at diploma mobility there is a lot to be gained there. Our high quality of education (the main pull factor for the Netherlands) does not help here. Students wonder why they should study elsewhere if it is ‘fantastic’ here. A possible solution is to combine study programmes, where students study partly in the Netherlands and partly abroad.

Institutes should also look at their facilities. Can they accommodate the students, for example? Housing issues, unfortunately, are often one-sidedly and negatively linked to international students, while these are issues that apply to the whole of the Netherlands due to shifts in family size, migration, housing construction in relation to CO2, and demographics. What also comes into play, for example, is what the catchment area is that the higher education institute focuses on. If every institute focuses on their own region, even then there are quite a few institutes in the Netherlands, especially in the south and east, that have a region going beyond the national borders. And then, as in Maastricht, for example, you certainly do not focus specifically on Dutch students. In addition, institutes can vary significantly in their approach to choices regarding their students' career prospects. You can aim for a career perspective that is more aligned with the Dutch labour market, but also one that is more internationally oriented. And there are other factors to consider as well.

Nuffic by no means says that "as many students as possible should come to the Netherlands".

Are there any blind spots in internationalisation at higher professional education institutes?

There are major differences between universities of applied sciences. Some are deliberately engaged in internationalisation and have an internationalisation strategy embedded in the broader institutional strategy. There are also institutes where internationalisation is something separate, or just the icing on the cake.

If you look at the sector in its entirety, participation in European Universities is really lagging behind. Not every university of applied sciences has to do it, but I doubt if it is always a conscious choice not to do it. European Universities collaborations are complex and intensive, and perhaps other forms of partnerships are a better fit for an institute, but I do not think there are enough real analyses being made at this point. Decision-making in this regard cannot be organised as a study programme or a domain, but must be undertaken at the level of the entire institute. Moreover, it requires investments in brainpower, manpower, and finances up front.

The European Universities alliances are not just isolated initiatives, but part of an increasingly European approach to the development of education. The Education Council has issued a recommendation entitled Active in Europe (March 2023, www.onderwijsraad.nl/publicaties/adviezen/2023/03/09/actief-in-europa), in which it notes that the Netherlands, particularly the government, is too much on the sidelines when it comes to educational developments in Europe. Traditionally, education was something where the EU member states were in the lead and where the EU had little say. That is shifting. The European Commission, the European Council and the European Parliament develop all kinds of initiatives in Europe to set out more joint policies. The council recommends drawing up a strategic agenda that provides clarity about the Netherlands' ambitions for European education policy. Because regardless of what we want as the Netherlands, things are simply happening at the European level and have an undeniable effect on what we do in the Netherlands. Germany, and, in particular, France are very focused on it. The European Universities initiative originally came from Macron and was intended as an excellence initiative. From France, the idea was: we have to compete with universities in Asia and the US and play all balls to excellence. I think we in the Netherlands are looking much more for a balance between excellent education and a generally high quality.

As a result, we stand, as it were, somewhat amazed at what is happening without taking enough action to express what we truly want. When the Netherlands has the European presidency again in 2029, will we have a plan of what we would like to get done in the field of education in those six months? We will have to start doing that today because it will take years. We must be more active, develop and elaborate ideas, find supporters, and co-direct which way it goes. This is also what happened with Macron's European Universities initiative. I would like to challenge ourselves to start now with what the Netherlands would like to achieve during our next presidency.

Do you see any other important developments that institutes should respond to towards the future?

Lem van Eupen

I think that we also need to start looking far more at things like microcredentials. We mostly work, especially in higher professional education, toward learning outcomes for a profession. If you start looking at lifelong development, we need a lot more flexibility. See what is happening at MIT and Harvard in this area.

Another aspect is the role AI is going to play in education, both positively and negatively. I recently attended a presentation about a system that allows you to have completely individualised learning pathways. A lecturer becomes more of an online coach who, based on students' portfolios and interests, offers individualised subject matter again. It has a high science fiction content when you first see it, but things might go much faster than we think now. All technological developments, especially AI, raise many new ethical questions. How technology can add value and where it might get in the way is an important new theme in Nuffic's strategy. We are now thinking about students coming to the Netherlands for an education institute, but will our education look like this at all in 2030, let alone in 2040?

To conclude, what would you like to bring as a focus to all the current discussions?

Whether it is about issues in education, in general, or around internationalisation, let us jointly ensure that the narrative of the added value of international experiences is not overshadowed by matters such as housing problems or the English language. It should primarily be about personal and professional development, about the enormous added value in broadening your own view, and about how these things enrich the Netherlands.